December 7, 1941 may be a date which will live in infamy, but December 7, 2018 will be a date that will bring closure to a family that’s been waiting for nearly 80 years.

The 1941 Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor took more than 2,000 lives; many victims were never recovered. Among those missing was 24-year-old Durell Wade.

Durell Wade

The Calhoun County native had skipped college to enlist in the Navy at an office in New Orleans. He was serving as an aviation machinist on the USS Oklahoma when it was attacked by Japanese aircraft.

For more than 75 years, Wade was just a memory shared by family members in stories and letters. His nephew, Larry Durell Wade, was born a year after the attack.

“I have his name and my grandson has his name, so it’s in three generations of family. Still, Uncle Durell was just an idea from Pearl Harbor,” said Wade, a retired psychiatrist living in Baton Rouge.

However, a few years ago, Wade’s surviving family received news that his remains may have been recovered. They submitted DNA for testing and in the spring, they learned the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency had identified their relative’s remains. Their lost sailor had been found.

“Never expected anything like this,” said Wade.

Wade’s remains will be flown to Memphis and brought to Pryor Memorial Funeral Home in Calhoun City for a Dec. 7 service at 11:30 a.m. A procession will then carry him to The North Mississippi Veterans’ Memorial Park in Kilmichael. The service will take place on the 77th anniversary of the attack.

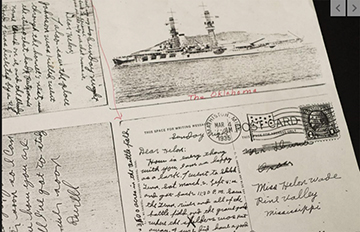

U.S. Navy’s recovery effort of the USS Oklahoma is shown in this photo. Five torpedoes from Japanese aircraft struck the battleship, which capsized in less than 12 minutes, trapping hundreds of sailors in their battle stations below deck. The attack killed 429 men on the Oklahoma.

Durell Wade was born in 1917 and raised in the Slate Springs area. Larry Wade’s research on his uncle revealed him to be a cheerful person who loved to joke and laugh. Late in her life, Durell Wade’s oldest sister, Orena, said he “loved his life aboard the USS Oklahoma (and) bragged that it could not be sunk.”

Wade, who was not married, had written home on Sept. 27, 1941, pleased to report that he had passed tests to be promoted to chief aviation machinist mate.

“In one of his letters, he mentioned his fiancée had broken up with him,” Larry Wade said. “He last saw her when he was an aviation machinist’s mate third class, and he wanted to propose to her but he knew he could not support her on the kind of income he had then. Right after that, she sent him a ‘Dear John’ letter and she married another guy. He mentions that in one of his letters.”

On Dec. 7, 1941, five torpedoes from Japanese aircraft struck the battleship, which capsized in less than 12 minutes, trapping hundreds of sailors in their battle stations below deck. The attack killed 429 men on the Oklahoma.

Those who perished inside the overturned ship remained there for more than a year before the ship could be righted. Remains that were recovered were hastily buried, said Chuck Pritchard, public affairs director for the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency.

After the war ended in 1945, remains were disinterred to identify them using forensic methods available at the time. Thirty-five were identified, and the rest buried again at The National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific, also known as the

Some of the postcards Durell Wade sent back home while serving aboard the USS Oklahoma.

“Punchbowl,” in Honolulu.

In 2015, remains from the Oklahoma were disinterred again for DNA testing. That’s when the Wade family was contacted to provide DNA samples.

So far, 146 remains from the Oklahoma have been identified. It’s a tiny fraction of the roughly 72,000 unaccounted-for military losses from World War II, but it’s meaningful to each family, Pritchard said.

Larry Wade and his family met with Navy representatives in August where they received an inch-thick notebook that included details of how the DPAA identified the remains. The notebook also had copies of letters between the Navy and family members that revealed something living family members never knew — that the family erroneously had been told that Durell Wade had survived before authorities confirmed his death.

“That stirred the family up quite a lot,” Larry Wade said.

The Navy will pay to have Durell Wade’s remains returned and buried.

“I’ve learned a lot about him (by) reading and talking to family members,” Larry Wade said. “He’s come much more alive as a person.”

Wade’s name is recorded on the Courts of the Missing at the Punchbowl, along with the others who are missing from World War II. A rosette will be placed next to his name to indicate he has been accounted for.

Editor’s Note: This story was compiled from a story by The Advocate in Baton Rouge, a report issued by the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency in Washington, D.C., and a collection of materials submitted by Dr. Larry Wade.